Immortal words spoken by Nelson Mandela, architect of the South African Freedom Movement, during his visit to India in 1990. The two sentences sum up the significance of Mahatma Gandhi’s years in South Africa, and the extent to which his experiences in that country shaped his vision, and thereby, the direction of India’s struggle for Independence.

My trip to South Africa in April 2004 coincided with the 10th anniversary of South Africa’s freedom from apartheid. It was for me a voyage of discovery in more ways than one. I was traveling to a land which had been the crucible of the Mahatma’s philosophy of non-violent resistance to injustice. By a strange coincidence, Southern Africa Zambia, to be precise), was also the place of my birth, over 30 years ago. A land I had not set foot upon, for 27 years.

On April 271h, 2004, South Africa celebrated a decade of its existence as a ‘rainbow’ nation. A nation where the colour of the skin would not determine one’s position and standing in life, or deprive one of political or economic opportunity. The main celebrations were held at the Union Buildings in Pretoria. I recall a beaming, if slightly frail, Nelson Mandela, helped up the steps, into the central plaza, even as a song was hummed in his honour. I could not help but think, in the same breath, of South Africa’s “Madiba”, and our very own “Bapu.” It was then, that the full extent of the parallels between India and South Africa, and their struggles for freedom, became apparent to me. Before me, I saw the outpouring of love and respect, from people irrespective of their colour or creed, for the man who had forged Africa’s most prosperous and vibrant nation, bringing it out of strife and disarray, through the principles of non-violence. The very principles that Mahatma Gandhi had evolved during his twenty-two year stay in that country.

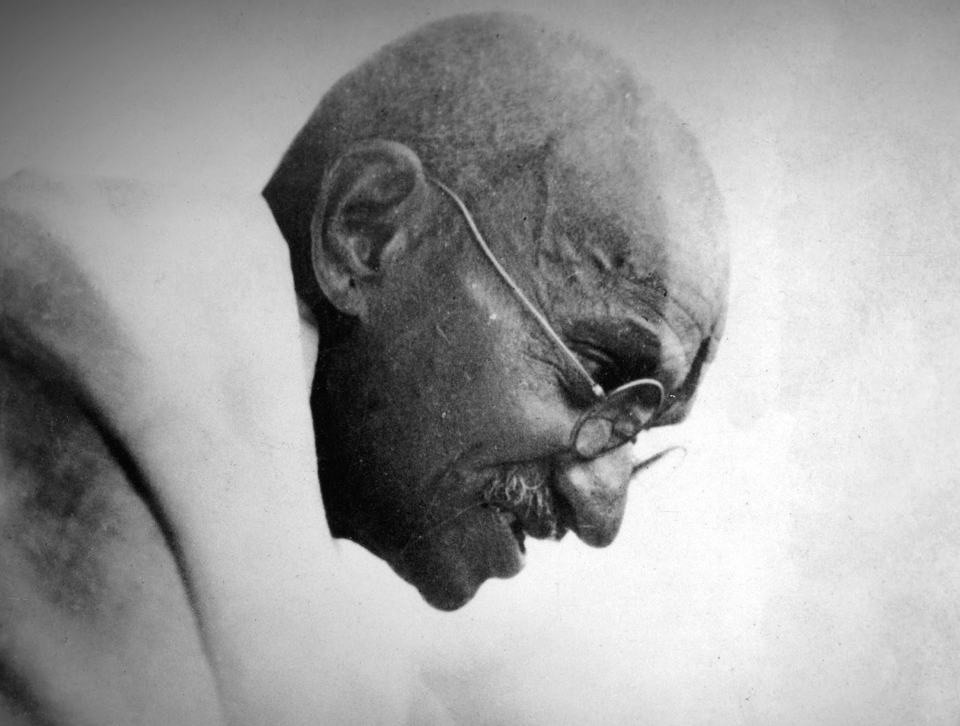

The same evening in Pretoria, I met Mr. Max Sisulu, son of Walter Sisulu, one of the closest associates of Nelson Mandela. Reminding me of the “Madiba’s” quote on the Mahatma, Max Sisulu went a step forward. In a voice that quivered with pride and affection, he said, “The Mahatma was ours. We gave him to you. But he remains ours first.” South Africa’s largest city, Johannesburg, lies just sixty kilometers south of Pretoria. At some point in the 1890s, it would have been possible to see Mahatma Gandhi, dressed in flowing legal robes and clasping a book, striding across Johannesburg’s Government Square. The area now goes by the name of Gandhi Square. And that image of a young and determined lawyer has been captured in a bronze statue. The statue stands tall on Gandhi Square, where the old law courts used to be; and not far from where Gandhi’s offices were. The larger-than¬life statue depicts Bapu as a young lawyer—as he was known in South Africa. It is indeed, a far cry from the stereotypical image of him as an old man wearing white robes and round spectacles. Former President Nelson Mandela said in a message read at the unveiling: “A hundred years ago Gandhi became the first person of colour to practise law in Johannesburg. Gandhi’s offices and the old courts are long gone. But here too, Gandhi paved the way for others.”

Also in Johannesburg is ‘South Africa’s new Constitution Court. This has been built on the site of the old native prison, where Gandhi and Mandela were both imprisoned at different times. It was in 1906, that the Asiatic Law Amendment Ordinance was passed in the province of Transvaal. This law proposed that Indians and Chinese were to register their presence in the province, giving their fingerprints and carrying passes. The protest to the act united the two communities and they decided to oppose the Ordinance by peaceful methods. Protestors got together, and a passive resistance was born. Gandhi spoke to the protestors, with the theme of “violence begets violence”. Protestors then marched through Johannesburg. They were arrested and thrown into prison at this very native jail. It was a place where Gandhiji was sentenced to spend time on four different occasions. And Prison Number Four is where, to this day, a portrait of the young Gandhi, stands testament to the Mahatma’s incarceration.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi had of course, arrived in South Africa on the 23 May,1893. It was in the port city of Durban that he had landed. A city, which even in the twenty-first century, instantly evokes memories of our very own Mumbai. A bust of Mahatma Gandhi today greets all visitors to the grand building of the old Durban Railway Station. It was from here, on the 7 June 1893, that Gandhi embarked on a fateful train journey, which was destined to change not only his own life, but consequently the course of world history. On a wintry Transvaal night, he was dumped unceremoniously onto the platform at Pietermaritzburg station for refusing to downgrade from a ‘Whites Only’ first-class compartment. A young lawyer had been thrown off a aain. A railway journey had been abruptly ended. But a much more momentous journey, the journey of the Mahatma, had begun. Gandhi’s first instinct was to return to India. However, he had no option, but to wend a bitterly cold night in the waiting room at Pietermaritzburg Railway Station. It was a night spent in reflection on the evil of racial prejudice. And with the first rays of the sun, came the realization that to flee would be cowardice. He vowed to stay and fight against inequality. Years later, he would acknowledge, that his active non-violence began from that date. Pietermaritzburg still retains its quaint railway station. And my visit to it was no less than a pilgrimage. The spot on the platform where Gandhiji was forced to alight is clearly marked, as are the benches within the waiting room where he spent the cold night. It was in 1904, that Gandhiji decided that the Indian Opinion, his weekly paper, should be printed at a farm away from the city of Durban. He purchased an estate in Natal province, twenty kilometres from Durban. This would be a place where everyone would labour, and draw the same salary. He called this the Phoenix Settlement. The Phoenix, of course, was the mythical bird that rose from the ashes. The place, as Gandhiji purchased it, has been described as desolate, overgrown with grass and trees, and snake infested. It suffered from severe winters as well as water scarcity. In this inhospitable area came and settled some Englishmen, a few Tamil and Hindi speaking people, one or two Zulus, and six Gujaratis. Gandhiji, it is said, could not actually live on the land for long, but would visit it at frequent intervals. His visits were special occasions which the children of the Settlement eagerly looked forward to. He would laugh and play with them. The settlers would prepare special dishes, and eat together on Sundays. Gandhiji, it is also said, relished good food in those days. The press-workers did all the work in the press themselves, bringing out the Indian Opinion. On nights when the final printing was done, they would need to stay up all night. To encourage them, kheer would be served.

By another of those strange coincidences that seem to create the parallels between South Africa and India, the tenth anniversary of South Africa’s freedom, was also the centenary year of Phoenix Settlement. I recall the place as a vibrant active example of community life. I stood and gazed upon a grand bust of the Mahatma. I walked in and out of the small huts and rooms, and tried to conjure visions of Gandhiji walking in and out of them, a century ago. My thoughts were interrupted by a frail old gentleman, dressed in a neat suit and tie. He introduced himself as Jayantibhai Desai, grand nephew of Kasturba Gandhi. And his voice shook, as he pointed out the very room, where once upon a time, “Ba” had cried on his grandmother’s shoulder. Gandhiji had asked Ba to participate in cleaning the community toilets. Those were momentous times indeed. At the southern tip of the African continent, Bapu, the Father of our Nation, fashioned a potent instrument, that decades later, would bring freedom to South Asia. And decades later still, another apostle of non-violence, known as Madiba to his people, would use the same instrument, to lead his diverse people, to a united, prosperous future. Already, in South Africa, signs of the prosperity are evident. The inter-mingling of races is apparent on the streets, from Pretoria, to Cape Town to Durban to Johannesburg. And on the expressway that links Jo’burg to Pretoria, a prominent local politician, who incidentally, is of Indian descent, pointed out the gleaming new headquarters of South Africa’s fastest growing company. I was intrigued to learn, that the name of that company was Sahara Computers, and it had been established a few years ago by one Mr Gupta, who had come to South Africa, from his native town of Saharanpur in Uttar Pradesh. I ventured into the building, and within the boardroom of Sahara Computers, I saw a microcosm of the rainbow nation that South Africa has now become. Fashioned in South Africa. Used in India. And used again in South Africa. Non-violence has created a miracle. Twice over. And across two continents, two nations continue their journey, in the footprints of the Mahatma.